DOI 10.24411/2413-046Х-2020-10005

STRATEGY EUROPE 2020 TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE INCLUSIVE INNOVATIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

СТРАТЕГИЯ ЕВРОПА 2020 НА ПУТИ К УСТОЙЧИВОМУ ИНКЛЮЗИВНОМУ ИННОВАЦИОННОМУ ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКОМУ РАЗВИТИЮ

Issa Nauma, PhD student of the Department of International Economic, Plekhanov Russian University of Economic Moscow, Russian Federation 115093, Stremyanny Lane, 36, Moscow, Russia; E-mail: nouma.issa@yahoo.com

Исса Ноума, Аспирантка кафедры мировой экономики, Российский экономический университет им. Г. В. Плеханова, РФ, г. Москва

Summary. This article is devoted to explore the steps to achieve sustainable European future by implementing the strategy Europe 2020 which is based on Lisbon Treaty. the ten year ambitious plan aims for a structural adjustment in which economic growth, social cohesion and environmental protection go in close association and are mutually reinforcing. The analysis focuses on five main areas: R&D expenditure, gas emissions and renewable energy, employment rate, primary and tertiary education, and risk of poverty. the analysis leads to the conclusion that, even though the strategy 2020 is not delivering its goals in two main areas: risk of poverty with a gap of 20.7 million people from the target set and spending on R&D with 0.97 percentage points below its target for 2020, however, the rest of strategy objectives was reached

Аннотация. Данная статья посвящена исследованию шагов по достижению устойчивого европейского будущего путем реализации стратегии Европа 2020, основанной на Лиссабонском соглашении. Десятилетний амбициозный план направлен на структурную перестройку, в рамках которой экономический рост, социальная сплоченность и охрана окружающей среды тесно взаимосвязаны и взаимно усиливают друг друга. Анализ сосредоточен на пяти основных областях: расходы на НИОКР, выбросы газа и возобновляемые источники энергии,уровень занятости, начальное и высшее образование и риск бедности. Проведенный анализ позволяет сделать вывод о том, что, несмотря на то, что Стратегия 2020 не обеспечивает достижение своих целей в двух основных областях: риск бедности с отставанием от установленного целевого показателя на 20,7 млн человек и расходы на НИОКР на 0,97 процентных пункта ниже целевого показателя на 2020 год, однако остальные цели стратегии были достигнуты

Keywords: Lisbon, financial crisis, Europe 2020, development, smart sustainable and inclusive growth, renewable energy.

Ключевые слова: Лиссабон, финансовый кризис, Европа 2020, развитие, умный устойчивый и инклюзивный рост, возобновляемые источники энергии.

The worldwide financial crisis in 2009 was described as the most cruel crisis since the great depression of the 1930s [13]. It started as a mortgage crisis in the USA and propagated internationally leading into a collapse in the global banking system which was followed by an international economic downturn and the great recession [15]. the global economy including the developed countries struggled to handle out the outcomes of the crisis which blot out years of growth progress socially and economically, reveled the structural weaknesses in the largest advanced economies, left the whole world facing meager challenges and stating the need of transformation towards more stable future[3]. The Europe Union which is considered the second largest reserved and second most traded currency after the USA, with estimated net wealth equal to 25% of the 317 trillion$ global wealth[8], was as a whole vulnerable to the crisis for many fundamental reasons like the culture fragmentation, clumsy policy making, and low fertility rate, in addition to the meager challenges like globalization, climate change, and ageing population which left the EU in argent need for a turning point not only to recover from the crisis, but also to come out stronger. The EU reflection on the financial crisis was by creating a strategy leading into a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy providing high levels of productivity, social coherence, and green growth [2].

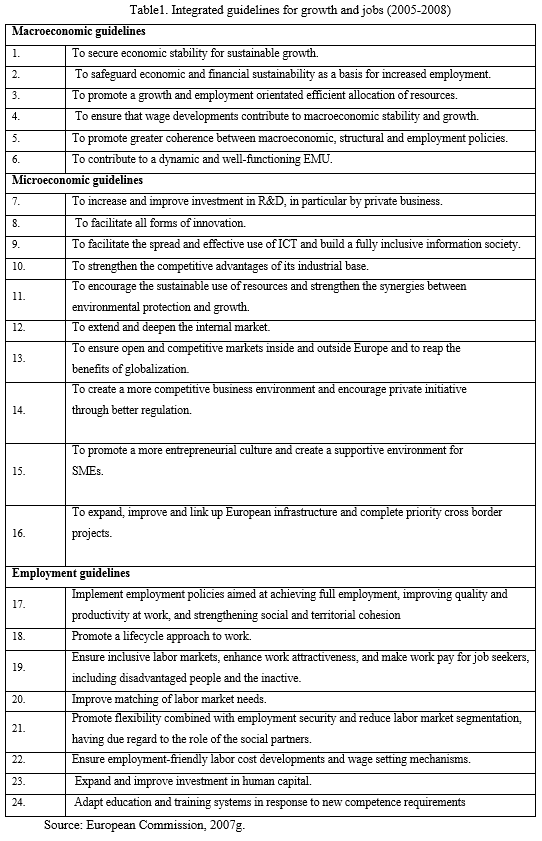

Europe 2020 was created and developed based on the Lisbon agenda which was a new European perspective in the time of the transitions from nationals currencies into euro and the preparations of the EU enlargement. It was a development plan from 2000-2010 for the EU economy, launched at the European council meeting in Lisbon March 2000 and aimed to deal with the low productivity and the slackness growth in EU. The goal was to create the most competitive and knowledge based economy in the world based on three key roles: innovations, R&D, and environmental renewal [4]. Lisbon strategy was shaped as a 10 years reform program with annual monitoring reports on progress to find a resolution for the raising of economical challenges such as the domination of the USA and Japan in the sphere of information and communication technologies. At first the strategy was based on two diminution, concentrating on integration of new polices socially and economically to be implemented by the state members, but after one year another pillar has been added: the environmental diminution. In 2005 a mid-term evaluation for the five year period was lunched and the outcomes was not as expected, the strategy was falling behind its goals(i.e. 70% employment rate, and 3% of GDP spent on R&D) which suggested the need of changes in some policies. Lisbon strategy was mainly a learning experience, kept gradually developing throughout the whole period to a complex structure with multiply goals , and faced many obstacles such as the growing process of the union at that time (i.e. from 15 state member to 27 since 2000; the euro-area expanded from 12 to 16 member); the fact that many of the policy areas involved Member State competences made the implementation of the strategy more complicated, and hinted that in order to achieve results, close cooperation between the EU and Member States would be required[14]. In 2006 a renewed approach for the agenda was lunched and set for three years cycle as a short term plan to guarantee more effective actions. The main priorities were to invest more on R&D and innovations, focus on labor market and business opportunities, climate change, energy policy, and to establish an effective partnership between the EU institutions and its member states. The recovery plan was promoted by incorporated a set of 24 guidelines for growth and jobs, economic policy guidelines (for macro-economic and micro-economic policy) and the employment guidelines (for the employment policy) which companied the general framework and previous polices within the renewed ones. In 2008 the EU council started the third period cycle of the strategy from 2008-2010 which included a minor adjustments of the 24 guidelines and global crisis management.

Lisbon strategy aimed mainly to modernize the EU social model, invest in human capital, integrate an economical and social policies, reduce the technology gap between USA, Japan and the EU and to pave the way into transition to a knowledge-based economy and society by implementing more efficient policies and creating more competitive and innovative economy throughout completing the internal market[9]. It was divided into three stages: the lunch of the first period between 2000-2004, mid-term evaluation, the reform strategy 2005-2008, and the third cycle from 2008-2010. An overall assessment of the strategy indicated that although the strategy did not delivered all its promising goals, nevertheless it had dramatic influence on the EU policy making by providing flexibility and dynamic adaptation to the emerging political challenges over time and smoothly absorbing new Member States as the Union expanded its membership. According to statistics indicators the EU employment rate reached 66% in 2008 from 62% in 2000, the total R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP only grown from 1.82% in 2000 to 2% in 2008, the official targets were 70% & 3% respectfully. Reforming the strategy after the first five years was huge factor in boosting the growth rate which was slow and almost near stagnation, the implementations of the renewed policies helped raising the euro zone GDP potential growth to 0.2% between 2005-2007, also a robust growth in employments rate was deducted reaching 64.6%[5]. These good results indicated the possibility of reaching the strategy aimed goals at the end of the time period epically that some of the member states was performing really well and had reached and beyond the set goals at the end of 2007; however, in 2008 the financial crisis hit hard and uproot most of these impressive results. Lisbon strategy during its process had to overcome a lot of core issues, one of the EU’s main challenges was not only narrowing the developmental gap with the overseas, but also reducing the gap between the old and new members. On the other hand, each member state was still building their ownnational innovation strategies and define their owntargets instead of gathering to produce a joint action, also the different conceptions and mechanisms of the welfare for the Member States made it difficult to agree on common direction in the social diminution of the strategy. Moreover it was determined that one of the most structural problems in the strategy was the lack of sufficient regulation, the weak and ineffective governance mechanisms represented by the Open Method of Coordination OMC which is a soft mode of governance over a centralized supranational method that allowed Member States to maintain their own structural arrangements and thus there were no institutional leadership to monitor progress and stimulate engagement[6]. To sum up, one can argue that even though Lisbon Treaty was not a huge success because of the unsatisfactory growth, the still productivity and competitiveness gap with US, the imbalance between economic efficiency and social equality, unmeet employment targets; however, on the other hand, with justification it cannot be denied that it was a success in its essence as a long term encouraging policy learning, planning, analyzing, coordinating, and also as a beneficial instrument in evolving economic reform and for that reason EU members were inspired to continue the Lisbon-type reforms within the newly adopted Europe 2020 strategy.

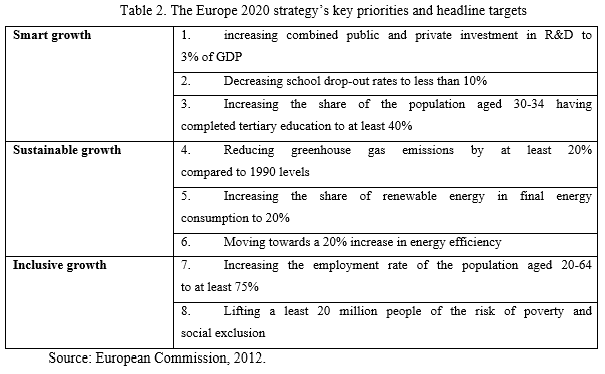

After a difficult start to the decade under the obscurity of the financial and economic crisis, Europe was ready to pursue and redress its development plans. On March 2010 the proposal of strategy Europe 2020 was introduced and discussed by the commission of European Council, and in June 2010 it was adopted. Coping with Lisbon flaws was one of the main priorities in constricting the framework of Europe 2020, the lack of coherence, well defined guidelines, governance, monitoring performance, sanctions, obligations, national policies changes, clear procedures and time management were all taking into considerations, it was determined to increase the strengths and decrease the weaknesses over the last decade along with building up the missing harmony. Strategy 2020 main aspiration was attempting to deliver high levels of productivity, employment, and social cohesion within the Member States, while making less impact on the natural environment, and dealing with the ongoing challenges of globalization, climate change, aging population, and the financial crisis. Thus the strategy primary anchor was to attain smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth in five thematic areas [16].

In addition to the quantitative evolvement of the old strategy by increasing objectives areas from two to five towards expansion interest in reducing poverty, climate change , and education, the EU commission also supported its five goals with embracing seven flagships initiative on: innovation union, youth, digital agenda for Europe, resource effectiveness, industrial policy for the globalization era, a protocol for a new skills and jobs, and the fight against poverty.

Coordinating the effort of EU member states was a crucial element in the success of the Europe 2020 strategy. To ensure this, The EU targets were interpreted into national level to reflect each member’s current situation and the level of aspirant they are able to reach as a portion of the EU whole effort to deliver Europe 2020. Moreover, the European Commission has also set up the European semester, an annual cycle of economic policy coordination that aimed mainly to foster structural reform, insure growth stability, and to prohibit excessive macroeconomic imbalances in the EU. The cycle included an annual growth survey, mechanism reports, publication of country reports, fact finding mission for the member states and submission of the national reform programs, and council discussions on country specific recommendations.

The European Commission carried out a number of evaluation reports on the EU cohesion policy which until 2010 concentrated on improving economic, social and environmental conditions within the European Union. The evaluations concluded that it would be more effective to focus on a few key priorities such as resources especially in the more developed regions because it will allows not only the member states but also the EU regions to build up a tangible impact through starting programs that identify a fixed number of policy preferences with a clear comprehension to how they will be achieved and how their achievement would contribute to the economic, social and territorial development of the EU regions and Member States[1]. At this point the importance of the Smart Specialization Strategies (S3) principle got more recognized by the European Commission because it aims to boost growth and jobs in Europe, by enabling each region to identify and develop its own competitive advantages and to manage a priority-setting process in line with national and regional innovation strategies[13]. The S3 principle represents a productive example of interaction between science and policy and was initially developed by the Expert Group ‘Knowledge for Growth’ in 2008 based on the innovation system research and theory applied at the level of regional systems of innovation (RIS) to enhance and incorporated regional economic transformation as a key principle of investment in research and innovation in the overall framework of strategy Europe 2020. The first progress into this direction was publishing the “Guide on Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization” In May 2012 which contains basic terms and principles to be followed in designing the smart specialization strategies. The next milestone was to work on the Implementing of the S3 principle taking into considerations the necessity of being pragmatic about it, namely building on policy-makers’ needs and on field evidence; being useful, meaning to create a relevant supporting tool; And being executive, by providing practical suggestions that can be immediately applicable. The implementation of research and innovation strategies was considered as an important step and key driver for the achievement of Europe 2020 strategy objectives by the EU policymakers from a regional perspective [7].

Since 2010, a fundamental progress and conclusive growth has been made in many areas including climate change through the increase in the use of renewable energy sources and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, as well as in the sphere of education where the EU is within reaching distance of their headline targets, but on the other hand the progress is less promising in developments of R&D investment and poverty reduction. The analysis in 2018 edition of ‘Smarter, greener, more inclusive?’ showed that the EU’s employment goal can still be reached if the growth recorded over the past few years continues. The highest employment rate since 2002 was recorded in 2017 at 72.2% up from 71.1% in 2016 and in 2.8 percentage points from the 75% strategy target. This rate also exceeded most non-EU G20 economies in the world in 2017, except from Japan and Australia. Regarding the employment group ages, the highest rate was recorded for people between 30 to 54 while the rate was lower for young people from 20-29. Group (aged 55 to 64) although their employment rate has grown continuously over the last decade, but it has remained low compared to younger age groups. Also from gender perspective, even though the employment gap has narrowed for all age groups since 2002 and in 2017 was at 11.5 percentage points, however the women employments rate remains lower than men[10].

Gross domestic expenditure on research and development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP has slightly progressed between 2008 and 2012, reach 2.04% in 2015 and has stagnated around 2.03% of GDP since then. By 2016 the EU was with 0.97 percentage points below its target for 2020 and in order to deliver the 3% of GDP final strategy goal a combined public and private R&D expenditure was needed taking into considerations that business enterprise share of the R&D performing sector in the EU account for 64.9% of total R&D expenditure while The shares of ‘higher education’ and ‘government’ sectors contribute less to the total R&D expenditure, at 23.0% and 11.2%, respectively.

The EU emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) had fallen to 22.4% By 2016, compared with 1990 levels which indicate that the EU is expected not only to reach but also to exceed its target of reduction GHG emissions to 20% by 2020[12]. The industrial sector share of total emissions reduction was the largest in 2016 even though it was still responsible of the most emissions in absolute terms over the time period between all sectors. Moreover the EU’s GHG levels of emissions per capita were much lower than the levels observed in major economies such as Australia, Canada and the United States, in addition to a significant progresses regarding the renewable energy was achieved especially in Transport and electricity sectors by using the bio-fuel (Solid, liquid and gaseous) that provided the biggest share of total renewable energy used in transportation, and for heating and cooling in the EU, and hydropower which remains the dominate technology in electricity sector; furthermore, the shares of solar and wind energy have raised essentially in the last decade. The share of renewable energy in gross final energy production was 17.0% by 2016 only 3.0 percentage points from the Europe target of 20% by 2020 and relatively high Comparing to other emerging and industrialized economies in the world. Also a visible progress was made regarding the 20% energy efficiency objective. The EU had significantly reduced primary energy consumption by 10% in 2016 less than in 2005 and globally only Japan had better results than EU by consuming 18.4% less energy in the same year[11].

One of the most important headlines of Europe 2020 was focusing on education. This target included: 1)achieving less than 10% of early school leavers between 18-24 year old especially for men because they are more likely to leave education earlier than women adding that early leavers face crucial problems in labor market and have big probabilities to stay inactive or unemployed; 2) increase the share of 30-34 year old who have completed tertiary education to 40%. Since 2008 the rate of early leavers dropped from 14.7% to 10.6% by 2017 and the share of people with high education improved reaching 39.9%, which indicate that Europe is steadily approaching its educational target even though it still have a gap with some major economies like USA, Canada, and Korea in that area[12].

The strategy Europe 2020 aims to reduce the number of People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 20 million till 2020 through focusing on: 1) the three commune forms of poverty: monetary poverty, very low work intensity, and severe material deprivation; 2) and The most exposed groups to the all three dimensions of poverty, in other words young people, unemployed and inactive persons, single parents, people with low educational, foreign citizens born outside the EU, and those residing in rural areas. The EU witnessed high growth of risk of poverty in the in the last decade due to the delayed social effects of financial crisis, namely almost every fourth person (23.5% of the population) in the EU remained at risk in 2016, about 86.9 million people, representing 17.3% of the total EU population, were at risk of monetary poverty while 39.1 million or 10.5% were affected by the second most common dimension of poverty the very low work intensity, and 37.8 million people equaled 7.5% of the total population in the EU were suffering from the third form of poverty or social exclusion severe material deprivation leaving the EU behind the strategy target by 20.7 million people. Thus, Significant additional efforts are necessary to close this gap by 2020 [12].

Economic growth, social cohesion and environmental protection along with a systemic change in policy agenda were the long-term objectives of strategy 2020 in which all the three above mentioned spheres go hand in hand and are mutually reinforcing in regional and state levels. The strategy 2020 delivered its targets in most areas especially in reducing emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) to 20% compared to 1990 levels and increasing the share of renewable energy in final energy consumption to 20%, also in education by decreasing school drop-out rates to less than 10% and increasing the share of the population aged 30-34 having completed tertiary education to 40%, and in employment by increasing the employment rate of the population aged 20-64 to 75%. However, much less success was found in the other two objectives: risk of poverty with a gap of 20.7 million people from the target set and spending on R&D with 0.97 percentage points below its target for 2020, thus a significant efforts are needed to close those gaps until the end of the strategy time period. Moreover, on the international level the EU 2020 strategy plays an important role in addressing the adopted 2030 Agenda by world leaders at the United Nations in September 2015 for Sustainable Development “Transforming our world”, the agenda is a set of 17 guidelines with 169 associated goals on development and thus sitting the EU on the right direction towards achieving a sustainable future by shaping its internal and external policies, research and innovation programs to balance a good standard of living for all Europeans, within the limits of our planet.

References

- Arnkil, R., Järvensivu V., et al. (2010). Exploring Quadruple Helix. Outlining user-oriented innovation models. Työraportteja 85/2010 Working Papers. Tampere, University of Tampere, Institute for Social Research, Work Research Centre. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265065297_Exploring_the_Quadruple_Helix

- Communication from the commission EUROPE 2020 A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, Brussels, 3.3.2010. https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf

- Eichengreen; O’Rourke (March 8, 2010). “A tale of two depressions: What do the new data tell us?”. URL https://voxeu.org/article/tale-two-depressions-what-do-new-data-tell-us-february-2010-update

- European Commission – Publications Office: Understand FP7. URL https://ec.europa.eu/research/fp7/pdf/fp7-inbrief_en.pdf

- European Commission. 2007b. Integrated Guidelines for Growth and Jobs (2008-2010).COM (2007) 803 final. Brussels. 11 December 2007.

- European Commission. 2010d. Commission Staff Working Document. Lisbon Strategy Evaluation Document. SEC (2010) 114 final. Brussels. 2 February 2010.

- Gianelle, C. and Kleibrink, A. (2015), “Monitoring Mechanisms for Smart Specialisation Strategies”: Joint Research Centre Technical Report, JRC 95458.

- Global wealth report 2018. file:///C:/Users/no3ma/Desktop/global-wealth-report-2018-en.pdf

- Presidency Conclusions, Lisbon European Council 23/24 March 2000. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_en.htm

- Sustainable development in the European Union. A Statistical Glance from the viewpoint of the un sustainable development goals, 2016 edition.

- Sustainable development in the European Union. A Statistical Glance from the viewpoint of the un sustainable development goals, 2018 edition.

- The EU Open Data Portal. http://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data.

- The Europe 2020 competitiveness report: Building a More Competitive Europe. Report World Economic Forum, Geneva (2012).

- Višnja Samardžija Hrvoje Butković (2010) From the Lisbon strategy to Europe 2020. the National and University Library, Zagreb, number 749222.

- Williams, Mark (April 12, 2010). Uncontrolled Risk. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-163829-6.

- Захарова Н.В., Лабудин А.В. Малое и среднее предпринимательство в европейских странах: основные тенденции развития // Управленческое консультирование. 2017. №12 (108)–. С.64-77.